Thuyền Nhân

Vietnamese Refugees, Human-Rights Policy, and Global Governance in Hong Kong

Ever since the Vietnam War’s conclusion, an outpouring of excellent studies on how the fierce fighting originated, plus every tiny detail at home and abroad during its course, have been produced by American academics and popular writers alike. Unfortunately, their narratives often pay scant attention to events after the U.S. retreat, overlooking the enormous human consequences that the Indochina conflicts entailed elsewhere. The global refugee crisis that followed is gravely understudied; even in Hong Kong, where this became the worst humanitarian disaster in history — a legacy of some of the Cold War’s bloodiest episodes — is a forgotten story today. Talking about the 1970s and early ′80s, instead, routinely conjures up images of fabulous entertainment, rapid urbanization, and economic boom. This collective memory is only partial.

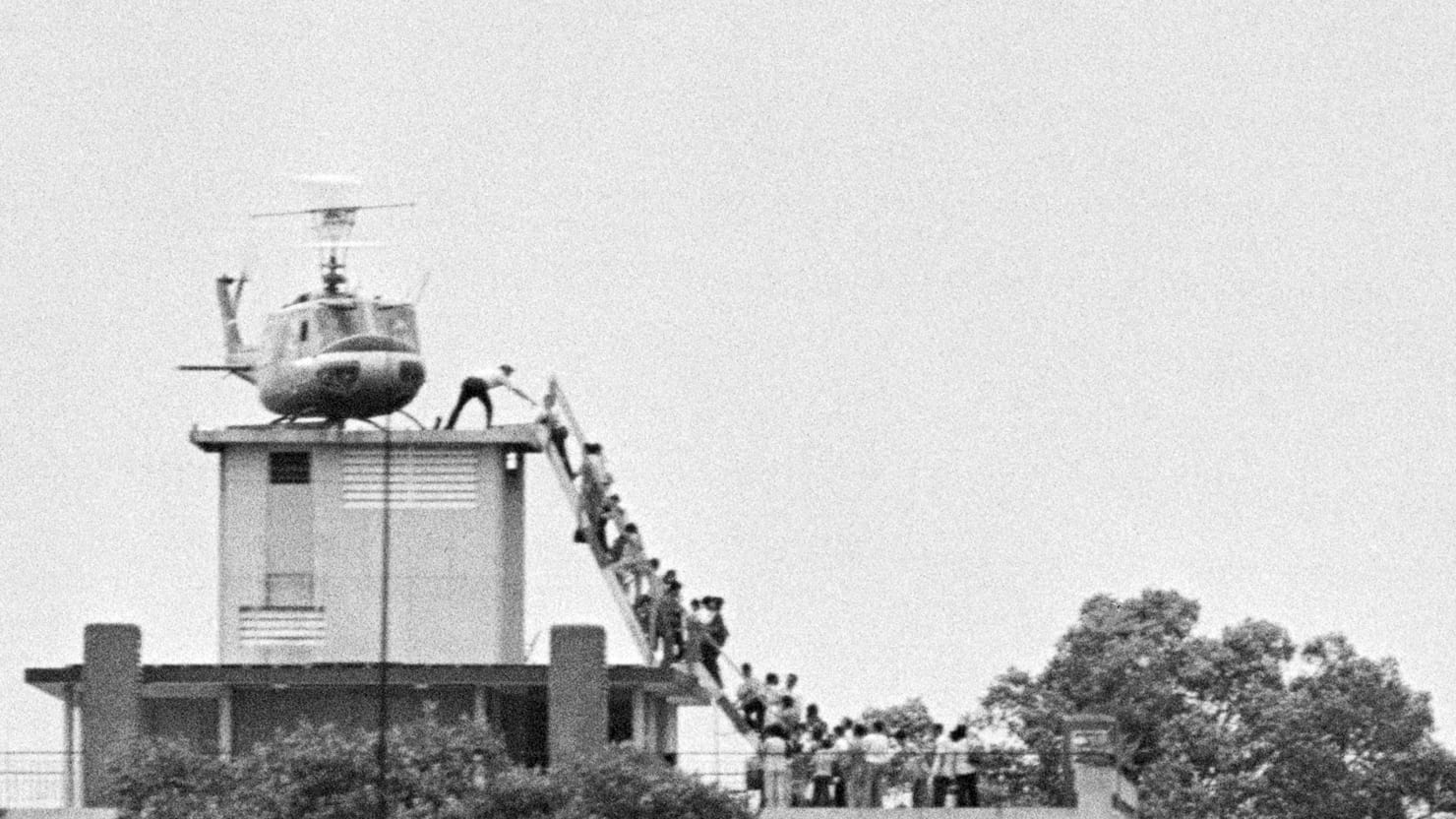

On May 5, 1975, just five days after the dramatic fall of Saigon, a ship carrying 3,743 fugitives from the defeated South Vietnam arrived in Hong Kong. Although the U.K. maintained its official neutrality, the colony had been indirectly involved in the Vietnam War for well over a decade, providing strategic facilities for the U.S. war effort and hosting American servicemen on rest and recuperation. Already too densely populated, however, it wasn’t ready to accept large numbers of civilian exiles. Following much deliberation, the colonial administration — as a reliable Cold War ally of the capitalist West sympathetic to the South’s failed crusade to build a non-communist state — nevertheless agreed to welcome the first batch of those who would come to be known as the boat people. With that, a controversial quarter-century endeavor to rescue, by some estimates, up to 200,000 Vietnamese refugees, had commenced.

Back in Vietnam, most individuals older than 30 had lived more than half of their lives almost incessantly in bloodshed; those born after 1945 had never experienced lasting peace. Families were shattered. Still, the survivors never gave up their yearning for a better future and took a risky gamble to sail across the South China Sea. An untold number of them were hurt or dead. Others who made it to the shores of Hong Kong against all odds found themselves interned in closed camps where they waited, sometimes in vain, for acceptance into First World countries like Canada, Australia, France, or the largest recipient among them, the United States. The catastrophe continued throughout the Third Indochina War — between China, Cambodia, and Vietnam chiefly as an escalation of the Sino-Soviet split — and reached its peak in 1979, when Hanoi’s Sinophobic decrees forced Han ethnic minorities, even those from the former North, to flee.

London’s response, like many things British, was full of contradictions. The Hong Kong government was certainly accustomed to handling defectors from communism: Many from China had flooded into the colony since 1949, and the famous Touch Base Policy was implemented in 1974 to authorize their immediate repatriation unless they could reach the city center — south of Boundary Street — without being caught, in which case they’d be eligible to remain legally and seek employment. Their Vietnamese counterparts were given no such option, as the British sought assistance instead from the Geneva-based U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. Unlike neighboring countries like Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand, Hong Kong maintained its “first port of asylum” status and never turned a boat away (at least until the late 1980s), even though it had no desire to set the fugitives free, hoping instead to accelerate their resettlement. The predicament nevertheless lingered on until after the end of British rule, when Hong Kong’s last detention facility was closed in May 2000 by the new Beijing-backed government.

I’m currently in the early stage of researching this project as my Ph.D. dissertation for Georgetown University under the direction of James A. Millward. My interest began in October 2017 while mining the British National Archives, where I stumbled upon a wealth of recently declassified — and largely untapped — files on the topic. I expect more to be made available in the months and years ahead. I’ve also conducted further research at the University of Toronto’s Richard Charles Lee Canada-Hong Kong Library, where I was a visiting scholar in 2017–18. I look forward to consulting more secondary sources, conducting original oral history interviews, as well as accessing archival materials in Hong Kong, Britain, Vietnam, Canada, the U.S., and perhaps Switzerland, Australia, and France.